How does one describe Hayy ibn Yaqzan — literally, Living, Son of Awake? This Arabic work of fiction, whose renderings, paraphrases, shadows, and footprints are found in Hebrew, Latin, English, German, French, Spanish, and elsewhere, is in the generic sense a piece of fiction no doubt. But what kind of fiction? It has been described as a “novel,” “fable,” “edifying tale,” “allegory,” “parable,” and often “philosophical romance.” Then, following the Latin Hayy tradition, it is also called a pioneering work in “autodidacticism,”— a word that combines two Greek words autós (“self”) and didactikos (“teaching”), thus meaning “teaching oneself without the guidance/mediation of an external teacher.”

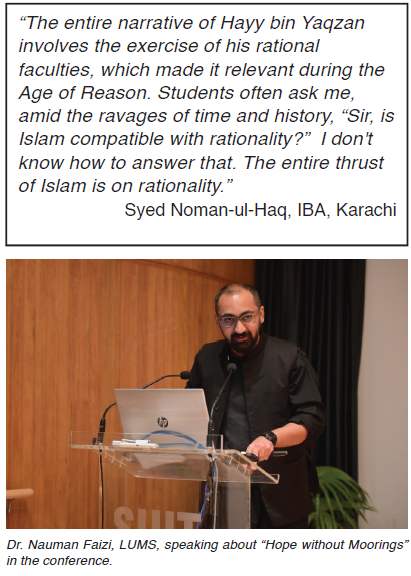

Nor is the substantive question straightforward: Is the Hayy a work of rational philosophy? Or is it a Sufi discourse in which philosophy functions merely as a ladder to reach mystical heights? In other words, is the author seeking ‘ilm, discursive knowledge, or is he rather a wayfarer traversing his path towards the station of ma‘rifa, what may be described as gnosis? Then, a related question: Is his fundamental inspiration Greek philosophy, in particular Aristotle and Plato, in whose thoughts he is often drenched? Or does this inspiration ultimately happen to be the indigenous Islamic intellectual and spiritual ethos, given his running citations and frequent implicit references to the Quranic text, among other Islamic scriptural sources? Indeed, these complicating issues make the work ironically a richer historical and literary phenomenon, opening up many new vistas that bring before us dazzling sights.

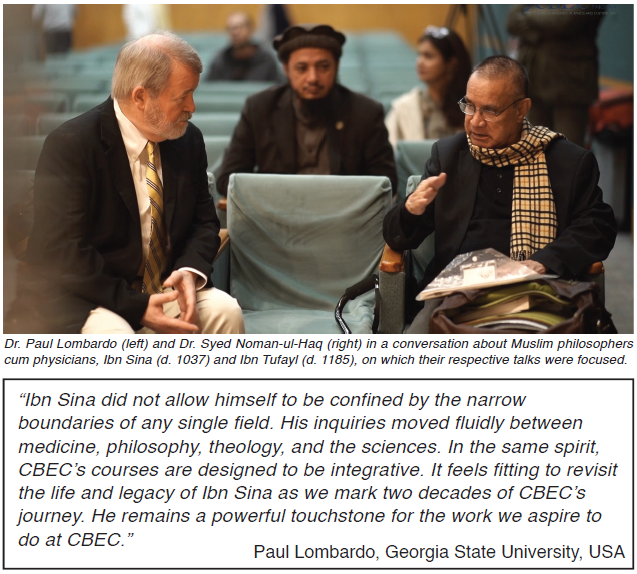

The Hayy was written some 900 years ago in the early 12th century in Andalus, Muslim Spain. Its author, the philosopher and theologian Ab Bakr Ibn Tufayl (Latinised, Abubacer Aben Tofail) was a vizier of the Almohad (al-Muwahhidn) ruler Ab Ya’qub Yusuf, whom he also served as a physician. This polymath author of the Hayy, who died in 1185, was a great supporter of his younger contemporary, Ibn Rushd, the redoubtable philosopher held to be the greatest Aristotelian in the whole history of philosophy. It was Ibn Tufayl who had urged Ibn Rushd to work on Aristotle and to purify this Greek giant from the obscurities of his commentators. Given Ibn Rushd’s decisive impact on European philosophy, only this act is enough to give Ibn Tufayl a high place in world culture Hayy ibn Yaqzan is the name of the protagonist in Ibn Tufayl’s tale. This human was born in an uninhabited island in the Indian Ocean, so goes the story, without human begetters. But his birth is explained not in transcendental-symbolic terms, but in naturalistic-physical terms, in terms that may legitimately be described as “scientific.” This was the case of spontaneous generation that comes to pass through the mixing of natural elements and confluence of natural forces — the underlying element being the mud of the shore. Hayy is then suckled and reared by a gazelle. So a feral human being grows up.

The main thrust of the tale is autodidacticism — learning without an external teacher but through one’s own rational powers. Through the exercise of reason alone, then, Hayy discovers the real facts of the world, finding out the workings of the cosmos and arriving at philosophical truths; and indeed by the sole means of his inborn intelligence he acquires biological knowledge, ethical knowledge and, ultimately, knowledge of God, the “Necessarily Existent Being.” We may well characterize Hayy’s mode of inquiry as embodying a “scientific method” by means of which he carries out all his discoveries of the physical world’s operations and of virtuous social conduct. Since he grew up in the wild among animals, and his moral sense remained pristine without any family or communal biases, he also develops an ecological sensitivity, caring about all creatures around him and not arrogating himself higher than any other being in the natural environment. Hayy here stands as a leader of our contemporary environmental concerns.

The use of reason here takes many forms of manifestations— sometimes Hayy makes logical deductions from self-evident premises in an Aristotelian vein; sometimes he makes “inductive” generalisations; here we see him contemplating in the style of Plato and the Sufis; there we find him making systematic observations. When his mother gazelle dies, he dissects her body and proceeds precisely like a biologist to discover the centrality of the heart for life. Hayy’s ascent on the steps of cognizance manifests a paradigm case of self-tutelage, autodidacticism that is, a process that leads him finally to “the Cause of all things,” “the Maker,” and then he declares more in the Sufi mode than the rationalistic:

He is being, perfection and wholeness. He is goodness, beauty, power, and knowledge. He is He [huwa huwa]. “All things perish except His face.” (Quran, 28:88).

Note the Sufi cry, “He is He!” The story moves on: when Hayy is a fully mature man, he experiences his first human encounter. A man called Asal visits his island. Who is this stranger? He came from another island, but one that sustained a human population. After some initial struggle to make Asal overcome his phobia of the unknown fellow man, a struggle during which Hayy even uses brute force to subdue the evading stranger, the two become friends. Asal then teaches Hayy his human language, and they are now able to converse.

They compare notes about their cosmological ideas, their ethical principles, their notion of upright life, and, of course, about God. Lo! Hayy finds that they are identical; what Asal had learnt through the guidance and instruction from an external teacher, from some kind of an apostle, was no different from the body of knowledge that Hayy had gained by himself through exerting his own innate faculties of reason. And here Ibn Tufayl makes that resounding declaration that constitutes a core doctrine of Islamic philosophy — that reason and revelation lead to identical truths. The two have cognitive equivalence. What religion teaches by means of parables and stories, and what philosophy yields through the exercise of reason — these two are substantively the same. Indeed, Muslim philosophers recognize a higher status for prophets on account of their direct, instant knowledge of the truth, given that they are “gifted ones.”

Hayy ibn Yaqzan’s historical impact on world intellectual culture was massive; in fact, mind-boggling. We hear its chimes all over Europe — in pure philosophy, in science proper, and in educational doctrines, not to speak of literature and that liberating genre of fiction. In 1671, Edward Pococke the Younger translated the Hayy into Latin from an Aleppo manuscript copied in 1303 that is now held in the famous Bodleian collection at Oxford University. Pococke called it Philosophus Autodidactus. And then, it feels like a continuous spring shower.

Just three years after the Latin translation, we saw the first English translation by George Keith, and another in 1686 by George Ashwell. Then we meet Simon Ockley, who renders the Hayy into English directly from the Arabic, The Improvement of Human Reason: Exhibited in the Life of Hai Ebn Yokdhan, published in 1708. Now the famous philosopher Spinoza, a pioneering foundational figure of the Enlightenment, finds the Hayy standing in such harmony with the spirit of the times, that he convinces his friend Johannes Bouwmeester to translate it into Dutch. More translations were to come and scholars say that the Hayy had become a “bestseller” during the Scientific Revolution.

The tide of the historical vicissitudes of the Hayy rises. In 1719, it charms Daniel Defoe and the world saw Robinson Crusoe modelled after it, set likewise on an island, although our Arabic tale may not have been the only source for Defoe. Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book is yet another ramification from the same literary seed. One recalls that Robinson Crusoe is considered to be the first novel in English, just as its source Hayy has the acclaim that it is the world’s first philosophical novel with an “enormous impact” on the Enlightenment. And so the spirit of Hayy lives in our modern sensibilities.

Turning to the domain of intellectual history, the chimes of the Hayy are to be heard all over. The founder of empiricism in modern-day philosophy, John Locke, happened to be a student of Pococke, the Latin translator of the Hayy, and knew his teacher’s translation since he refers to it. But what is more, historians say that the English philosopher’s classic tabula rasa (“blank slate”) theory — the theory that the human mind at birth is a blank slate — is inspired by the Hayy; this observation is highly plausible. Historians have also traced the Arabic tale’s diffusion in, and in many cases, direct impact on, the thought of Robert Boyle, Voltaire, and even Karl Marx. This includes Emile, or On Education of Rousseau.

But far away in time from all of this is a medieval Hebrew translation of the Hayy carried out in Muslim Spain. The scholar Rudolph Altrocchi in 1938 provided a groundbreaking body of historical evidence: he demonstrates that Dante read this translation. Yes, indeed, there are many crucial parallels between the Hayy and the Divine Comedy, such as one ecstatic and “gorgeous vision” of Hayy — a vision whose sharp reflections are to be found in Dante’s description of Paradise.

A very large number of scholars have made Ibn Tufayl and his Hayy their subject of research; L. Goodman is one of them, whose translation of the text I have reproduced. Here, one recalls an article published in The Guardian many years ago, written by M. Wainswright. It was called, ‘Desert Island Scripts: Footprints of a 12th-century Muslim Robinson Crusoe.’ Wainswright tells us that the drizzle continues until now.

A longer version of this essay by Syed Noman-ul-Haq previously appeared in Dawn on Sunday, May 22, 2016.